Only a third of Jews living in the UK have faith in God, as described in the Bible, yet ‘non-believers’ make up more than half of paid-up synagogue memberships, according to data from the JPR National Jewish Identity Survey

Dr David Graham

and test your family's knowledge of Jews worldwide while reading the Haggadah!

Dr David Graham

The late Chief Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks was a committed Arsenal fan. In 1990, he and George Carey, then Archbishop of Canterbury and another Arsenal supporter, attended a match together. It didn’t go well. Together, they witnessed their team lose 6-2 to Manchester United in what was described as Arsenal’s worst home defeat in 63 years. The following day, a reporter impudently suggested that if the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Chief Rabbi between them cannot bring about a win for Arsenal, surely that proves that God does not exist conclusively? But in what has become a famous retort, Rabbi Sacks replied that, on the contrary, it proves God does exist; “it’s just that He supports Manchester United.”

The existence of God is, of course, an age-old philosophical question which I am happy to leave to the clerics and philosophers. However, the issue of belief in God is of great interest to social scientists, and data help us understand more precisely what people do and do not believe. A YouGov poll from 2020 found that half of all people in Britain do not believe in God, a fact which helps to explain the decline of Christianity in Britain over the last generation.

Of course, God is also central to Judaism. Indeed, according to the great medieval Jewish philosopher and commentator, Maimonides, one of the central tenets of Judaism is belief in God, for, as he argues, without God, how can there be a moral compass?

To this end, in our recent National Jewish Identity Survey, JPR asked 4,900 Jewish respondents to choose between three statements: ‘I believe in God as described in the Bible’; ‘I do not believe in God as described in the Bible, but I do believe there is some other higher power or spiritual force in the universe’; and ‘I do not believe there is any higher power or spiritual force in the universe’.

The results show that one in three Jews believe in God – about the same proportion YouGov found in the general population. But unlike the wider population, Jews are half as likely to be out-and-out atheists; just one in four Jews don’t believe in God or any other type of higher power or spiritual force compared with one in two generally. There are far fewer Jewish atheists because the ‘spiritual’ Jewish middle ground is more than twice the size of the middle ground in the general British population.

In the Jewish case, more than half (56%) of paid-up synagogue members do not believe in God, and nearly two in five Jewish atheists belong to a synagogue

Nevertheless, if only a third of Jews have faith in God, as described in the Bible, where does that leave Judaism? Is it inevitably on the same downward path as Christianity? Not necessarily. A key indicator of the decline of organised religion in Britain is ‘bums-on-pews’ – i.e. that only people who believe in God are likely to attend church. Even if that is true, it doesn’t seem to apply to Jews. In the Jewish case, according to the survey’s data, more than half (56%) of paid-up synagogue members do not believe in God, and nearly two in five Jewish atheists belong to a synagogue. Moreover, irrespective of whether they belong to a synagogue or not, two out of three (65%) Jews who don’t believe in God attend synagogue at least on the High Holy Days of Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. Jews, it seems, are pretty comfortable belonging without believing.

So why do the Jewish godless bother? To begin answering this question, we can turn to a classic study from the mid-1960s carried out by the renowned sociologist Marshall Sklare, together with Joseph Greenblum, of the Jewish residents of ‘Lakeville’ (a pseudonym for what was, really, a suburb of Chicago). The two scholars recalled hearing their respondents making comments such as “x is not a very good Jew”, or “y acts like a good Jew should act”, or “z thinks he’s a good Jew, but as far as I’m concerned, he’s not.” They decided to pose a question that Jewish social scientists have pondered ever since: What qualities do Jews think are necessary to be a ‘good Jew’? Their original list contained 22 items, but interestingly enough, none of them explicitly referred to God. So JPR decided to ask its British respondents whether they agreed or disagreed that ‘Belief in God is not central to being a good Jew’?

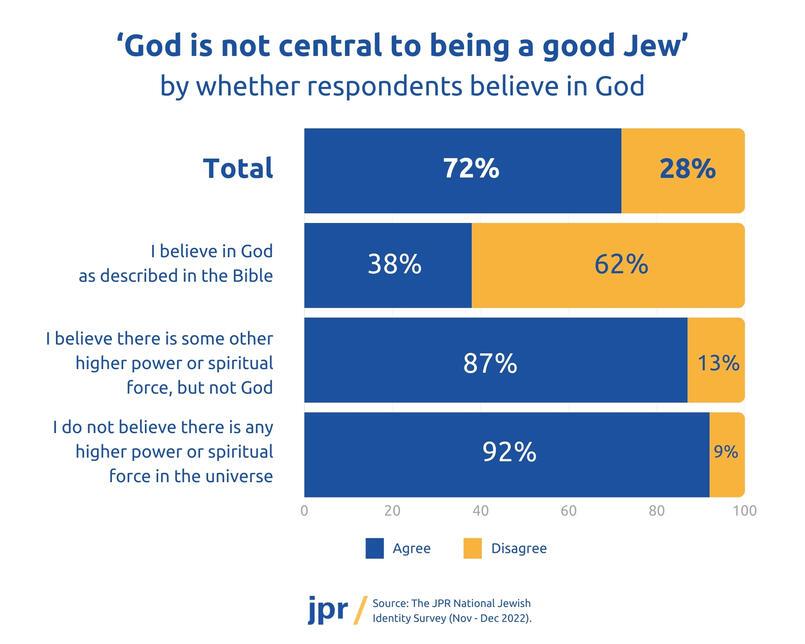

The results are enlightening, going some way towards explaining why Jews might belong without believing. A substantial seven out of ten Jews said that, in their opinion, belief in God is not central to being a good Jew. Jews who do not believe in God – the majority – believe it’s entirely consistent to be a good Jew without believing in God. To be fair, the minority of Jews who do believe in God are far more likely to say that God is central to being a good Jew. However, even among this group, almost two in five say it is not.

It is difficult to imagine the same response pattern occurring among Christian respondents. The reason for that is simple: for Christians, belief in God is a fundamental aspect of Christianity, and while one could argue that is also the case for Judaism, especially when it is constructed in terms of faith, the reality is that for Jews, Judaism – the religion – is just one part of the identity system to which Jewish people adhere. To be Jewish is to have a multi-dimensional identity incorporating traits such as culture and ethnicity, neither of which are God-dependent. And while there may be numerous traits Jews say are important to being a ‘good Jew’ - such as giving to charity, upholding strong moral and ethical behaviour, marrying another Jew, or volunteering - believing in God is not one of them. In short, whether God supports Manchester United or Arsenal, it is clear that a majority of British Jews do not support God as desribed in the Bible.

Senior Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow

David is a Senior Research Fellow at JPR, an Honorary Associate at the Department of Hebrew, Biblical and Jewish Studies at the University of Sydney...

Read more