Proportion attached to their Jewish and national identities rises by 5% between 2012 and 2018

Dr Jonathan Boyd

and test your family's knowledge of Jews worldwide while reading the Haggadah!

Dr Jonathan Boyd

Evidence from our study of European Jewish identity suggests that growing proportions of Jews in many parts of Europe feel able to comfortably integrate their Jewish and national identities. Our analysis, which draws on a model of acculturation developed by Canadian psychologist, John Berry, inputs variables measuring the extent to which individuals retain or reject their ‘native’ culture (in this case, their Jewishness), and the extent to which they have adopted or eschewed their ‘host’ culture (in this case, their attachment to the European country in which the live). Individuals with positive attitudes to both are categorised as ‘integrated’; those with negative attitudes to both are labelled ‘marginalised.’ Those with high attachment to country but low attachment to Jewishness are ‘assimilated’; and those with high attachment to Jewishness but low attachment to country are ‘separated.’

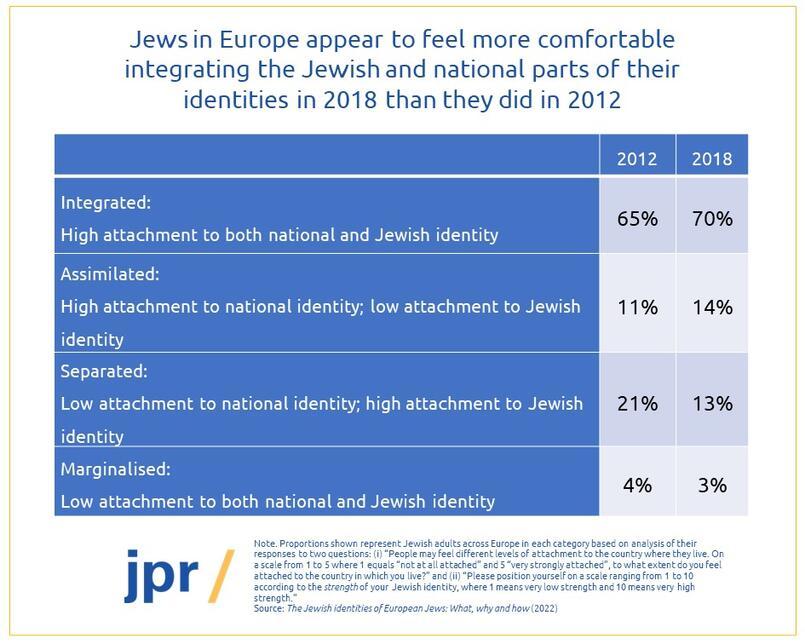

About two-thirds of Jews across Europe are categorised as ‘integrated,’ and that proportion appears to be growing. Based on the two studies JPR undertook for the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) six years apart, the evidence indicates a shift in that direction: where 65% of European Jews were found to be integrated in 2012, that had risen to 70% by 2018. Similarly, the proportion found to be ‘marginalised’ fell very slightly, from 4% to 3%, although differences at this level using these types of samples should be interpreted very cautiously.

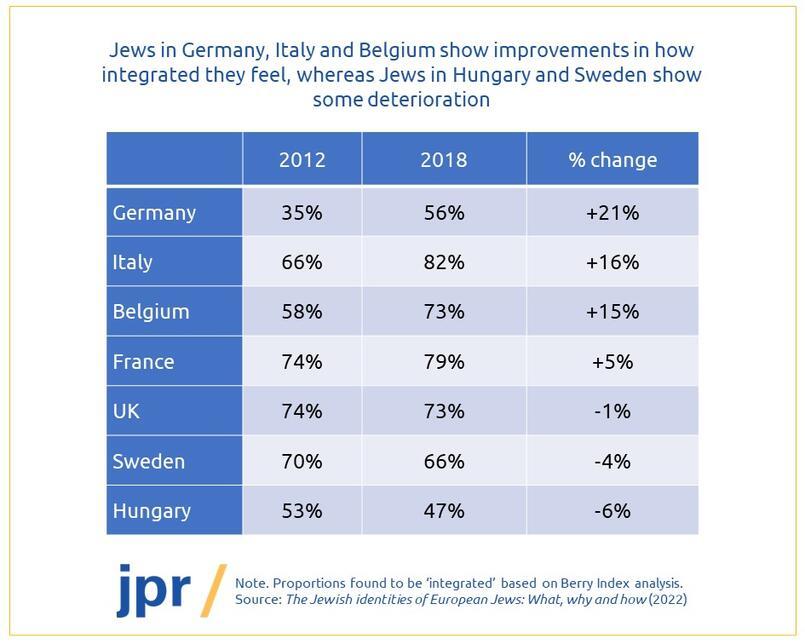

However, different countries show different trends. The most significant change can be seen in Germany, where the proportion found to be integrated rose substantially from 35% in 2012 to 56% six years later. The fact that both of these levels are lower than those found in most other countries listed is likely to reflect the nature of the contemporary German Jewish population: a major part of it is comprised of immigrants from the Former Soviet Union who arrived in Germany during the 1990s after the collapse of communism. Immigrant populations commonly take some time to feel high levels of attachment to their new host countries, but the shift over such a short period of time suggests that German Jews today increasingly feel at home in the country, and able to live their Jewish lives there.

However, the shift is similar in Italy where no such migration factor exists, and indeed in Belgium, where one might expect the large and growing strictly Orthodox population based in Antwerp to pull the population as a whole towards ‘separation,’ but the reverse is the case – where 31% were categorised as ‘separated’ in 2012, that proportion had fallen to 20% by 2018 (see main report).

The shifts found elsewhere are small, but taken at face value, are worthy of comment. The French Jewish community experienced several horrifying antisemitic attacks between 2012 and 2018, most notably the Hyper Cacher attack in January 2015, and saw Jewish migration rates to Israel spike in response, yet these data indicate that a higher proportion of French Jews feel integrated in 2018 than was the case in 2012. This may be because a large number of those feeling more separated or marginalised left the country in the interim, but equally it may be due to French Jews feeling more comfortable in the country, perhaps due to the generally positive and supportive response to antisemitism from the French government and European Commission.

It’s notable too that in the UK opinions appear to have barely shifted at all, in spite of the uproar from the Jewish community there about antisemitism in the opposition Labour Party whilst it was under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. Hungarian Jews show the largest shift away from integration, although in that case a major increase can be seen in the ‘assimilation’ category (see main report), rising from 20% in 2012 to 31% in 2018. The issue there appears to be less that fewer Jews feel able to integrate their Jewish and Hungarian identities, and more that higher proportions of Hungarian Jews are feeling disconnected from their Jewishness.

Executive Director

Executive Director

Jonathan has been Executive Director of JPR since 2010, having previously held research and policy positions at the JDC International Centre for Community Development in...

Read more