The notion of hiding our identity from others seems particularly pertinent this year, as nearly two-thirds of British Jews said they feel less confident revealing their Jewishness in public.

Dr Jonathan Boyd

Dr Jonathan Boyd

Jews traditionally wear masks on Purim. The reasons are varied: they range from the simple calendrical alignment of the holiday with Mardi Gras in medieval Italy, when masks were commonly worn, to the more spiritual idea that God ‘hides’ in the Book of Esther – the book read on Purim, and just one of two in the Hebrew Bible in which God does not appear at all. Other ideas include the notion that the Jewish queen in the story, Esther, hides her identity from her husband, King Ahasuerus, until she is compelled to reveal it to help save the Jewish People. Indeed, as many have pointed out, the name ‘Esther’ has the same root letters as the Hebrew word ‘hester,’ meaning ‘hide’ or ‘conceal’.

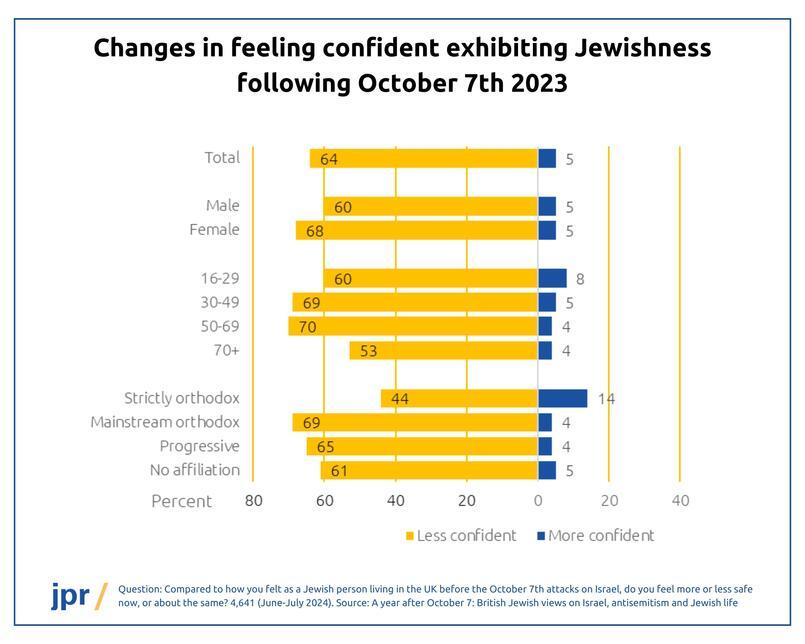

The notion of hiding our Jewishness from others seems particularly pertinent this year. When we asked British Jews in our summer 2024 national survey whether they feel more or less confident sharing their Jewish identity openly in public since the October 7 attacks in Israel – for example by wearing Jewish jewellery or revealing their Jewishness to colleagues or fellow students – close to two-thirds said they feel less confident, and just 5% said more. The remainder reported no change. In brief, it seems that many of us are hiding away on occasion, concealing our Jewishness for fear of how others may see or treat us.

The data vary a little by age and sex – women feel more vulnerable than men, and the middle generations more than the oldest (aged 70+) or youngest groups (aged 16-29) – albeit not dramatically so. The gender finding is unsurprising – in general, women tend to feel more at risk than men, and Jewish women are no exception. The age results are more intriguing. It seems that the ‘ambient antisemitism’ many Jews have experienced since October 7 has hit the middle generation the hardest; perhaps it has come as more of a shock to them than their elders, who still recall the everyday antisemitism of their youth, and their children, who have little personal memory to draw on. The middle generation has lived in probably the best era ever to be Jewish, in a country that has consistently been shown to have one of the lowest levels of antisemitism anywhere.

But other trends in public ‘mask-wearing’ by Jews are perhaps more revealing. There is an interesting denominational gradient, with slightly more ‘mainstream’ or modern orthodox Jews feeling less confident than progressive or secular Jews. Charedi Jews break the mould though; whilst the same fundamental shift in confidence has taken place, they are notably less likely to have been impacted in this way than other Jews. It is not uncommon to see this – interestingly, Charedi Jews tend to be more likely than most others to experience antisemitism, but least likely to let it affect them.

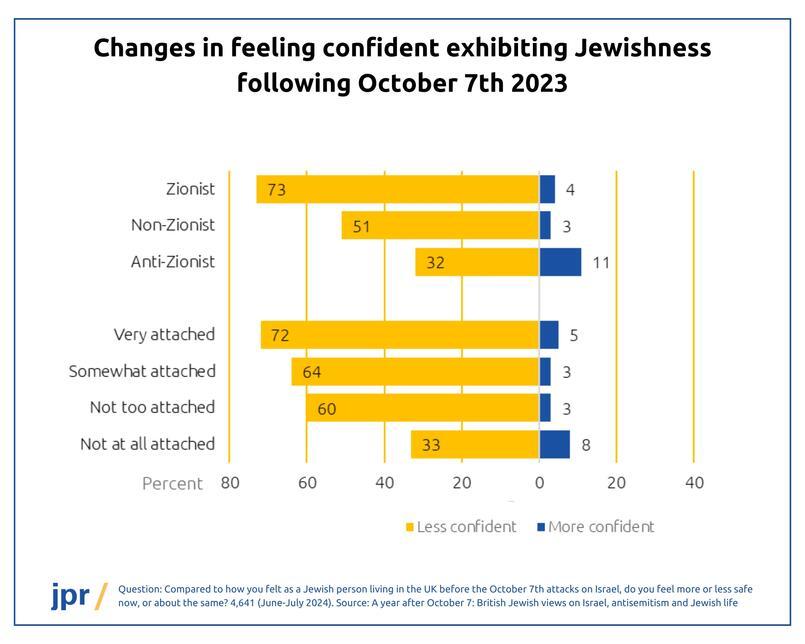

However, perhaps the greatest distinctions can be seen when examining the data by people’s connections with Israel and Zionism. Again, while all groups report an overall shift towards feeling less confident, self-identifying Zionists and those most attached to Israel have been hit the hardest. Only about a third of anti-Zionist Jews and those not attached to Israel at all feel less confident – the vast majority in these two groups (which overlap to some degree) report little change at all. By contrast, over 70% of Zionists and those most attached to Israel are showing signs of this type of vulnerability. The ways in which we relate to Israel, and the place it plays in our Jewish identities, are clearly related to our sense of Jewish self-confidence since October 7.

Yet overall, Jews of all denominations, beliefs and connections have been affected, suggesting that our tendency to ‘mask’ our Jewishness in some way, is rather common and widespread. Perhaps the question this Purim is less about when we put on our masks, and more about whether we have the confidence to remove them.

Executive Director

Executive Director

Jonathan has been Executive Director of JPR since 2010, having previously held research and policy positions at the JDC International Centre for Community Development in...

Read more