The UK Census identifies Jews by religion, ethnicity – or both. How does it affect the total count of Jews in the country?

Dr Jonathan Boyd

Dr Jonathan Boyd

In a David Baddiel-ian age, when it has become increasingly common to believe that 'Jews Don't Count,' community leaders and commentators have become ever more concerned about how data on Jews is gathered. There is growing disquiet, for example, that the national census of England and Wales only provides one question about religion, with one tick box allowing people to identify as Jewish, thereby potentially missing secular or atheist Jews who do not see their Jewishness as their religion. There are fears that such people will either feel compelled to select the 'No Religion' option or simply leave the question blank, thereby only appearing in official statistics as 'Religion Not Stated.'

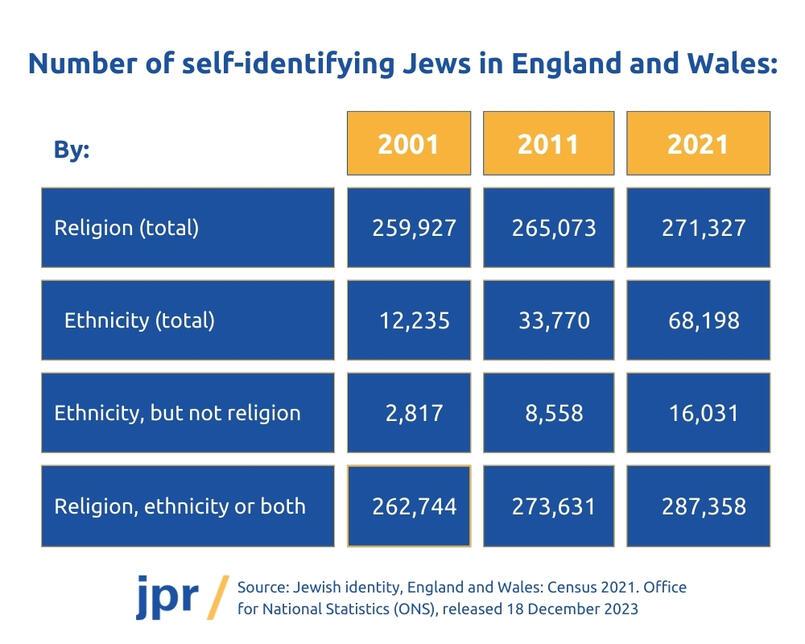

Yet some have found another way to identify as Jewish. Jews are increasingly choosing to use the ethnicity question – which fundamentally asks people to self-identify as White, Black, Asian, Mixed or 'Other' – to declare that they are Jewish. There is no Jewish tick box in that question, but 12,000 Jews wrote in that they were ethnically Jewish in the 2001 Census, and that number climbed to 34,000 in 2011 and again to 68,000 in 2021. Those are growth rates between censuses of 176% and 102%, respectively.

Does that mean that thousands of Jews are now being picked up in official data, who might previously have been missed? Not so fast.

The religion question actually works incredibly well. It enumerated 260,000 Jews in 2001, 265,000 in 2011 and 271,000 in 2021. Whilst these numbers should not be treated as Britain's final Jewish population count, parallel survey work indicates that they constitute somewhere between 85% and 93% of the total.

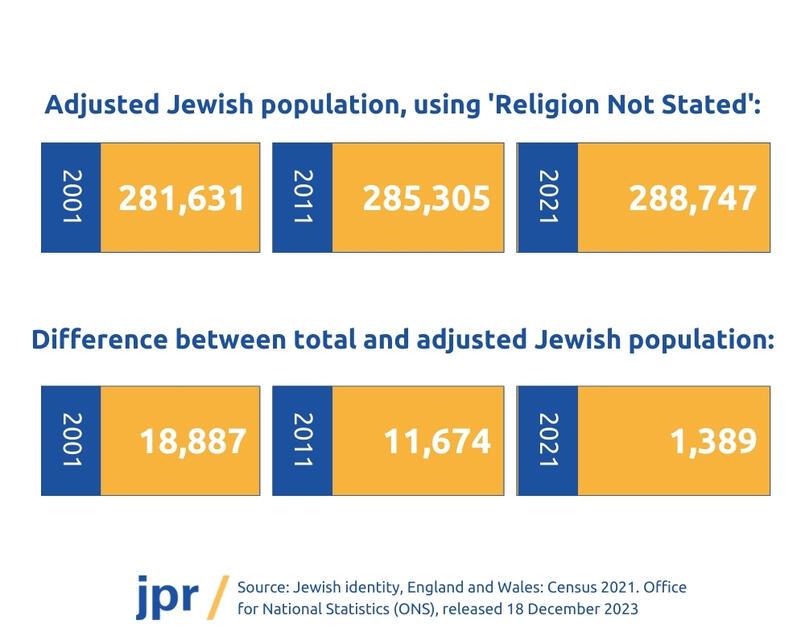

There is a simple way to adjust the Jewish population counts from the religion question to achieve better estimates. It involves assuming that Jews refuse to answer the religion question in the same proportions as the population of the country as a whole, then applying those national proportions for 'Religion Not Stated' to revise the Jewish estimates. Close analysis of both census and survey data provides sound justification for this method, producing adjusted estimates of 282,000 for 2001, 285,000 for 2011, and 289,000 for 2021, representing growth rates between censuses of just over 1% each time.

But what happens when we incorporate those Jews who self-identify as Jewish by ethnicity into our calculations? Given the dramatic growth of people choosing this, surely the increase over time is much sharper than that? Well, no.

In investigating the Jews by ethnicity data, it is critical to understand that most Jews who identify in that way also identify as Jewish by religion. There has been an increase in the number of people who only identify as Jewish by ethnicity, but it is nowhere near as large, climbing from 3,000 in 2001, to 9,000 in 2011, to 16,000 in 2021. It is these figures that can be added to the religion question counts to produce revised ones. When we do this, we find 263,000 Jews in 2001, 274,000 in 2011 and 287,000 in 2021.

Comparing these figures with the adjusted ones using 'Religion Not Stated' data to estimate the undercount, we see something very interesting. The gap between the two estimates was about 19,000 in 2001, 11,000 in 2011, and less than 2,000 in 2021. What appears to be happening is that the growing trend to identify as Jewish by ethnicity is largely plugging the gap between the enumerated religion counts and the adjusted ones. People's decision to identify as Jewish by ethnicity ensures that there is more data about them specifically, but it doesn't significantly affect estimates of Jewish population size overall.

There is further complexity. Some people who identify as Jewish by ethnicity select a religion other than Jewish in the religion question – most often Christian – so there are different views about whether they should be included in the overall Jewish population count. On the other hand, the figures above only account for Jews living in England and Wales; Jews in other parts of the UK are not included. Perhaps most importantly, there is growing evidence to indicate that Haredi Jews were significantly undercounted in the 2021 Census. Issues with online access, space on paper forms to accommodate large families, and perhaps reluctance to self-identify as Jewish at all, all appear to have taken their toll, so we know that they need to be accounted for more accurately.

Yet perhaps the most important insights from all of this are, first, that somewhat exceptionally in the Jewish Diaspora, the Jewish population of the UK is growing. The growth isn't dramatic, but it is clear. And, second, alongside that growth, we see evidence of Jews choosing to express their Jewishness more confidently – not simply by ticking an existing box in a question about religion, but by actively writing it into a question about ethnicity. Growth and self-assurance are, to my mind, rather good signs. And, contrary to some narratives, they may well point to increasing vitality and vibrancy in the British Jewish population going forward.

Executive Director

Executive Director

Jonathan has been Executive Director of JPR since 2010, having previously held research and policy positions at the JDC International Centre for Community Development in...

Read more