In Israel, about 70% of Jews fast on Yom Kippur. In the United States, the United Kingdom and France, the proportion is lower, but it is still way above 50%

Dr Daniel Staetsky

and test your family's knowledge of Jews worldwide while reading the Haggadah!

Dr Daniel Staetsky

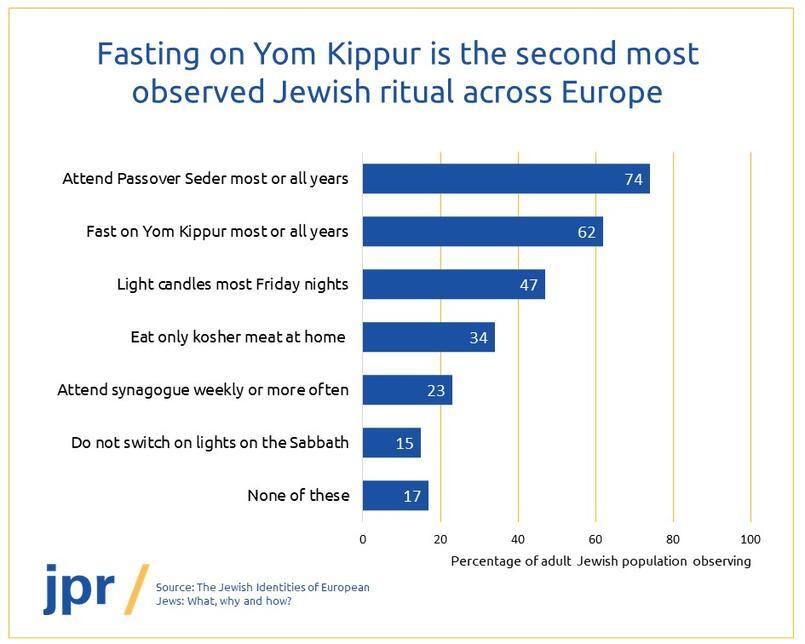

Fasting on Yom Kippur is one of the most commonly practiced rituals throughout the Jewish world, second only to attending a Passover seder. Remarkably, these two practices have managed to retain their lofty status under a wide variety of circumstances: from the religious wastelands of the Soviet Union, across the individualistic and secularised Western societies of today, and to the more traditionally inclined Israel. In Israel about 70% of Jews fast on Yom Kippur; in the USA, UK and France the proportion is in the range of 50%-60%. And observing the fast on Yom Kippur even occurs in the least religious Jewish circles: 25%-33% of Israeli, American and British Jews who are not involved in Jewish communal life or who explicitly identify as secular, fast on Yom Kippur.

25%, 50%, 70% - are these proportions large or small? For those concerned with the promotion of Jewish religious observance, they are probably all miserably low. Yet for anyone who has lived in a society with the lowest of the low levels, the proportions choosing to fast in Israel and the West are amazingly high. And I have lived in that lowest of the low world.

I was born and spent my childhood in the Soviet Union. My first ever visit to a synagogue took place on Yom Kippur. It was 1986 and I was 12 years-old. Mikhail Gorbachev had come to power in the previous year and, in hindsight, the days of the Soviet Union were numbered. But nobody suspected that in the autumn of 1986. For provincial Soviet Jews, it was business as usual. I accompanied my grandmother to the one and only, very old synagogue in our city. We made a somewhat common pairing at the time. Two types of people went to synagogue on Yom Kippur. The old, who came to pray as they did in their youth, and the very young, like myself. Both groups were considered to be beyond the danger zone of the Soviet authorities. According to the rumours, being caught going to a synagogue would lead to being fired from work and not being accepted anywhere else, pretty much like applying for a visa to go to Israel. Whether this was true or not I did not know, and I still do not know. All I knew was that pensioners could not be fired (anymore), and children could not be fired (yet). Those situated in-between did not go to synagogue, but some came together to break the fast in private houses. My aunt kept such an open house and served food to anyone who came.

8,000 Jews lived in my city, a large industrial centre with nearly one million residents, situated in the European part of the Russian Federation. Most, if not all, were Jewish evacuees from Ukraine, who managed to escape to Russia in the early days of the ‘Great Patriotic War’ (the Russian name for the Russian chapter of the Second World War), and their descendants. I estimate that no more than between 100-200 people came to the synagogue on Yom Kippur that year, and/or came to my aunt’s open house after prayers. And that range is a reasonable estimate of the proportion of Jews observing Yom Kippur in a large city of the Soviet Union, outside the traditional Pale of Settlement, in the mid-1980s: 1.2% – 2.5%. Close to nothing.

Has the situation changed since then? While levels of observance in Israel and Western Jewish Diaspora communities have been reasonably well documented by surveys, we do not have the same level of certainty in Eastern Europe. However, one thing is clear: Eastern European Jews are much less observant than Western European and Israeli Jews. The most recent investigation of religiosity levels among Jews in Hungary indicated that Yom Kippur is probably observed by no more than 5% of Hungarian Jews. A recent survey of communally involved Jews in Russian Jews found that about 24% of the respondents fast on Yom Kippur. Given the type of Jews responding to the survey – those most dedicated to Judaism and Jewish culture – it is likely that the real levels of Yom Kippur observance among Jews in Russia are probably close to the levels registered in Hungary. The gap in observance between Eastern and Western European Jewish communities is still tremendous.

There has been much talk about a national and religious revival in the post-Soviet space. These figures, while estimates, provide some sense of the reality, if translated into the proportions observing Yom Kippur in some way: an increase from 1%-2% to probably about 5% or so. So an increase, certainly, but current levels are still in single digits. Neither religiosity nor ‘Jewishness’ in Eastern Europe today has any real stigma attached to them, certainly not to the extent they did before the collapse of Communism. Thus, the very low observance levels in Eastern Europe can only be explained by the lasting impact of forced secularisation – something that the West and Israel never experienced.

In the three years that followed my educational mid-October walk from the synagogue to my aunt’s house, the Soviet system effectively came to an end. The collapse of the Soviet Union as a political entity took place shortly after. The majority of Soviet Jews left. About 1.5 million Jews lived in the Soviet Union at the time of the last Soviet population census in 1989, and 1.3 million left within a decade or so, two-thirds of whom emigrated to Israel. In Israel they formed the most secular group, yet their levels of observance today are much higher than the levels observed among Jews living in the Soviet Union and its successor states, then or now. Believe it or not, according to a recent Pew survey of Israeli Jews, 44% of Israeli Jews born in the Soviet Union now fast on Yom Kippur.

That is quite a transformation. The lyrical types among sociologists see it as a sign of a national and religious revival, while the more cynical types maintain that it is simply a reflection of their method of integrating socially and culturally. Either way, observance is observance, and, among former Soviet Jews in Israel as well as among others, it can stem from a variety of reasons. The ensuing similarity of lifestyles between immigrants and non-immigrants is not inferior because of ‘impure’ or complex motivations among the former. But it is difficult to argue with the revivalists: the Israel-born children of former Soviet Jews display levels of observance that surpass the levels typical of their parents and which are very close to the levels in the Jewish population of Israel as whole – according to the same Pew survey, about 65% of them fast on Yom Kippur. If that isn’t some indication of national and religious revival, I do not know what is.

Senior Research Fellow and Director of JPR's European Demography Unit

Senior Research Fellow and Director of JPR's European Demography Unit

Daniel holds a PhD in Social Statistics and Demography from the University of Southampton and a Master’s degree in Population Studies from the Hebrew University...

Read more