Climate change is the great global challenge of our age, but today’s Judaism appears to have little to say about it

Dr Jonathan Boyd

Dr Jonathan Boyd

Climate change is probably the greatest challenge of our age. The evidence for it is overwhelming, even though, when confronted with the science, it is often difficult to see the ever-diminishing rainforest for the felled carbon dioxide-releasing trees.

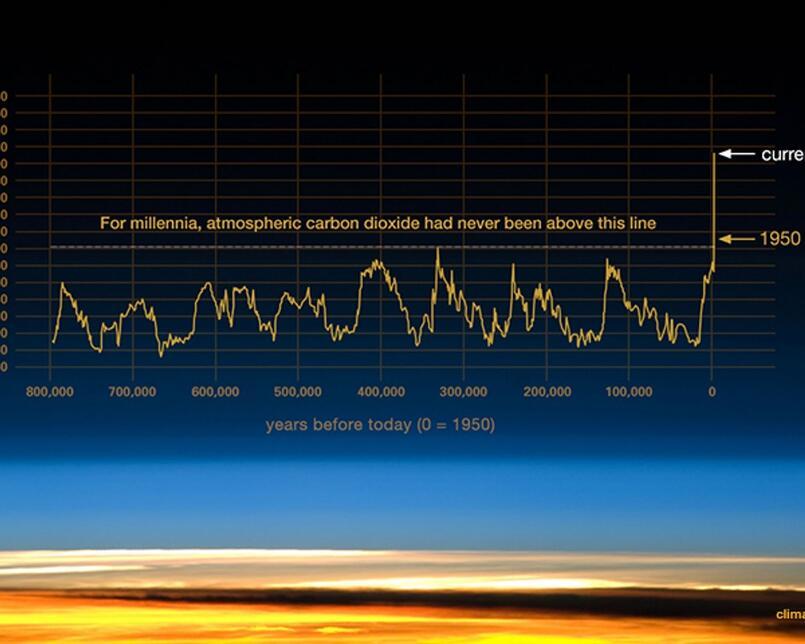

But of all the evidence out there, it is the historical data tracking how much carbon dioxide has existed in the atmosphere over time that is perhaps most arresting. Atmospheric levels of CO₂ have fluctuated between about 180 and 280 parts per million for the past 800,000 years. The lowest levels coincided with ice ages; the highest with much warmer interglacial periods. Such tiny differences have long held huge implications.

Yet the latest data show that there are currently about 416 parts per million in the atmosphere, easily the highest level ever recorded. The NASA chart showing this takes my breath away – the line fluctuates within that range of 180 and 280 for hundreds of millennia before suddenly, around 1950, breaking through the upper limit and continuing to rise sharply. The damage human beings have done to the planet in the industrial age is, quite literally, off the chart.

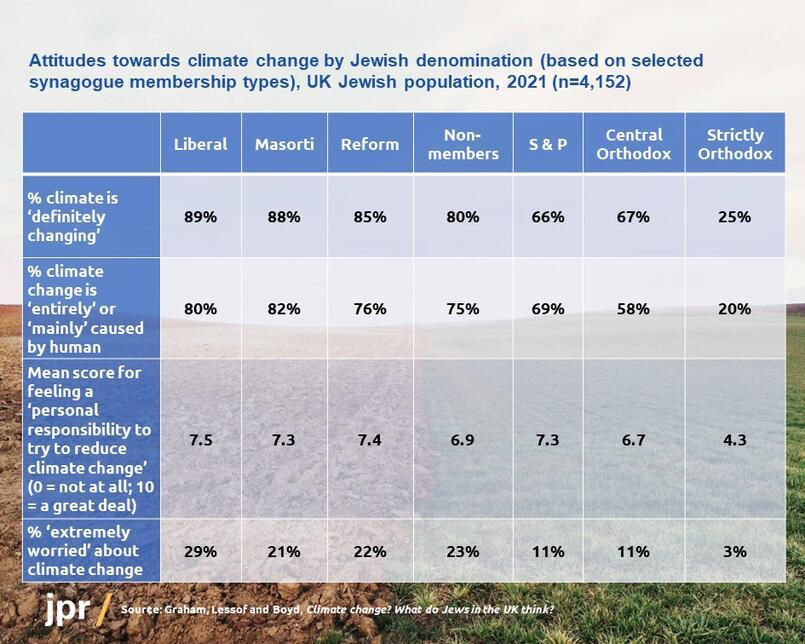

To what extent do British Jews understand or accept the scientific consensus on this? In general, they are quite climate aware – our data show that 92 per cent think that the world’s climate is either ‘definitely’ (69%) or ‘probably’ changing (23%). That said, Jews are more equivocal about the human role in it – just 63% blame human activity ‘mainly (50%) or ‘entirely’ (13%). Nevertheless, the overarching picture suggests that UK Jews are rather more climate conscious than the UK population in general.

Yet remarkable differences in attitude can be seen when the data are analysed by denomination. Members of non-Orthodox synagogues overwhelmingly believe that the world’s climate is changing – the proportions lie in the 85-90% range. But levels drop among modern Orthodox synagogue members to around 66% and fall further among haredi synagogue members to just 25%. The same pattern can be seen on other climate change measures too – whether it’s how responsible people feel personally to help address it, how worried they are about it, or whether they think human activity is to blame for it. So it’s progressives who lead on this, and haredim who lag behind.

However, by contrast, when we measure aspects of Jewish identity – belief, practice, community engagement and numerous other indicators – we find exactly the opposite. It is haredi Jews who consistently score highest, followed by the modern Orthodox, followed by the non-Orthodox.

Perhaps none of this is surprising. Yet it does raise a key question about the nature of Judaism today. How can it be that the most halachically-observant and communally immersed among us can be so sceptical, indifferent, or perhaps oblivious to a problem that so clearly represents an existential threat to human life? Why is the climate change issue so seemingly absent in the Jewishness they encounter? Surely Judaism should speak to this enormous challenge in some way?

Yet interestingly, when we conduct more advanced statistical analysis on the data, it looks like it’s not really Judaism that is influencing views among the non-Orthodox either. Their climate consciousness appears to come mainly from their secular education and their political views, which tend to be more left-leaning than those of the Orthodox. Non-Orthodox synagogues probably engage with climate change issues more than Orthodox ones, but they are preaching to the choir – non-Orthodox Jews were already largely on board before they even set foot in synagogue.

In short, wherever we look, Judaism itself doesn’t appear to be shaping our opinions or actions on this huge global issue. That should concern us – if the Judaism we encounter today doesn’t compel us to act on such a clear threat to human life, surely we need to ask ourselves some tough questions about how we are living and interpreting it?

Executive Director

Executive Director

Jonathan has been Executive Director of JPR since 2010, having previously held research and policy positions at the JDC International Centre for Community Development in...

Read more