For Diaspora Jews, Jewish festival observance requires six to twelve weekdays yearly. Unless you work for a Jewish organisation, this may well mean sacrificing your ‘secular’ leave days

Dr Keith Kahn-Harris

Dr Keith Kahn-Harris

They are over for another year: that intense succession of Jewish festivals – Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah – has been completed. This year, the intensity was heightened by the emotional anniversary of October 7 and the continuing war in Israel. But every year, the festival season can be daunting to contemplate, even if you only choose to participate in selected aspects of it.

JPR research demonstrates that 74% of British Jews mark Rosh Hashana in the home, and 57% attended at least one Rosh Hashanah service in 2022. More than half of Jews living in the UK fast on Yom Kippur every year, although that doesn’t necessarily mean they observe other aspects of it. So, the High Holy Days touched most British Jewish lives, even if observance of Sukkot and Simchat Torah was declined. The same variability can be found with the other Jewish ‘Yom Tovim’ (festivals) later in the year: Passover (Pesach) is marked by the vast majority of Jews in the UK and, indeed, worldwide; Shavuot, much less so.

The Yom Tovim are designed to disrupt the rhythms of our everyday Jewish lives, to take us to a different place, if only temporarily. Outside Israel, where Jewish festivals are often set as official leave days, that disruption is heightened by the unpredictability that follows from applying the Jewish calendar to the ‘secular’ one. Observing their strictures (even partially) may involve significant time out of work or school, depending on when the festivals fall. Those who do not work in Jewish communal organisations or have children in mainstream schools face a process of negotiation, preparation and catching up that can intensify the tensions between Jewish and secular life.

Jewish observance in Britain, particularly more traditional forms of it, requires planning ahead. The festivals’ peripatetic movement in the calendar can spring all kinds of surprises and dilemmas. But can we at least predict the degree of conflict between the Jewish and secular calendars?

This year in synagogue on Yom Kippur, I wondered whether, in a particular year, it is possible that all festivals might fall on a Saturday or Sunday or, conversely, whether it is possible for all festivals to fall on a weekday.

Given that there are thirteen Yom Tovim that traditionally observant Jews mark in the Diaspora (and eight that Progressive Jews mark), real issues are at stake here. Depending on the employer and labour laws, an observant Jew may be forced to take a considerable portion – or even all – of their paid holiday and may even be forced into taking unpaid leave, too. Conversely, those who are Jewish but not observant (or are not Jewish and who work for Jewish communal organisations) may benefit from a variable number of extra leave days per year (though they cannot choose their dates).

I asked the appropriately named Gabriel Gendler Yom-Tov – currently studying for a PhD in Maths and highly knowledgeable about the Jewish calendar – if he could calculate the maximum and minimum number of Jewish festivals that fall on a weekday. Here’s what he told me:

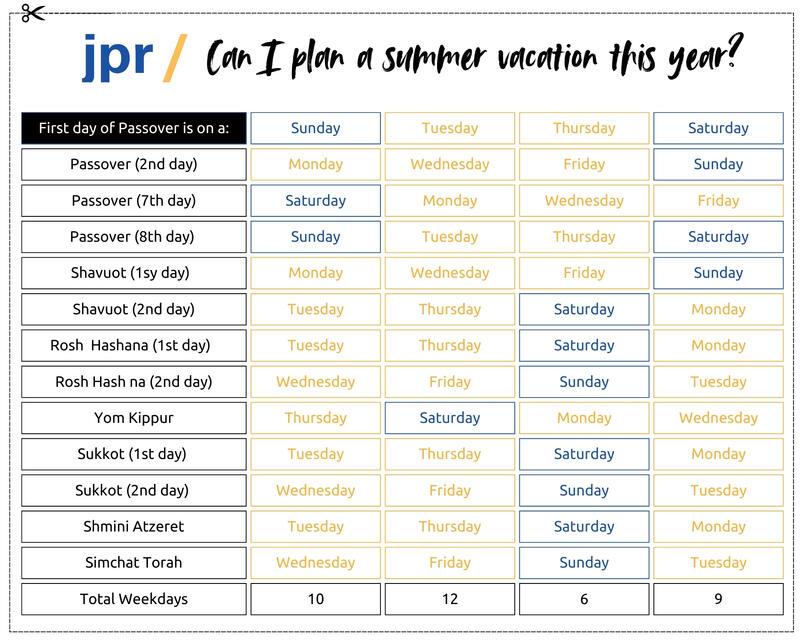

“Because all the flexibility in the Jewish calendar happens in the winter (Adar Sheni and Cheshvan and Kislev, the two months that can have 29 or 30 days), the most predictable part of the calendar runs from spring to autumn. Once you know what day Passover falls (and there are four options), you know everything about the Yom Tovim for that secular year.

“The rabbinical Jewish calendar is adjusted to align with the solar calendar in such a way that the first day of Passover can only fall on a Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday or Saturday. The last days of Passover, also Yom Tovim, would then fall on a day before (e.g. if the first day of Passover is Tuesday, the seventh is Monday), with the eighth day always falling on the same day as the first day, a week later. Shavuot is marked precisely fifty days after Passover, meaning it will always be a day after the first day of Passover, and Rosh Hashana, Sukkot and Shemini Atzeret are all one day after that. Yom Kippur is two days after Rosh Hashana.

“So Passover on a Sunday means that the second day of Passover, both days of Shavuot, and all seven of the Jewish New Year festival days fall on a weekday, totaling in ten days of weekday Yom Tovim; Passover on a Tuesday (like the year we’re just finishing) means a total of twelve days of weekday Yom Tovim (the most it gets); Passover on a Thursday (like last year) means a total of ‘just’ six days of weekday Yom Tovim, meaning we get to take that summer holiday in Aruba; and Passover on a Saturday means a total of nine days of weekday Yom Tovim.”

The bottom line is that it is impossible for all the Yom Tovim to fall on weekdays or for none to do so. For traditionally observant Diaspora Jews, festival observance requires at least seven and at most twelve weekdays – either of which cuts significantly into one’s annual leave allowance. Gabriel also worked out the figures for Progressive Jews, which require four to seven weekdays annually.

To make things even more challenging, Jewish festivals do not cycle through the calendar in predictable ways. Gabriel also pointed out that, interestingly, Passover on a Sunday happens only just over 10% of the time. In contrast, the other possible days are all almost equally likely at about 30% of the time. On top of that, the need to leave work early for the start of festivals at some points of the year at some latitudes, the practicalities of preparing for those times when Shabbat follows a two-day festival, the three other fasts other than Yom Kippur, the occasional coincidence of Yom Tovim with public holidays, and the complications that Jewish schools face in scheduling holidays, all make it even harder for Diaspora Jews. But who said Jewish life was meant to be simple?

For those of us who live in the Diaspora, Jewish festivals are not just opportunities for reflection, celebration, and prayer; they are also times when we confront the tensions and possibilities inherent in keeping pace with both Jewish and secular times.

With thanks to Gabriel Gendler Yom-Tov for his assistance with this article.

Senior Research Fellow and Project Director of the European Jewish Research Archive

Senior Research Fellow and Project Director of the European Jewish Research Archive

Keith Kahn-Harris has been Project Director of the European Jewish Research Archive since its inception in 2014, managing the collection process and analysing its holdings...

Read more