Christianity in the UK falls below 50% while 'no religion' continues to grow

Dr Jonathan Boyd

and test your family's knowledge of Jews worldwide while reading the Haggadah!

Dr Jonathan Boyd

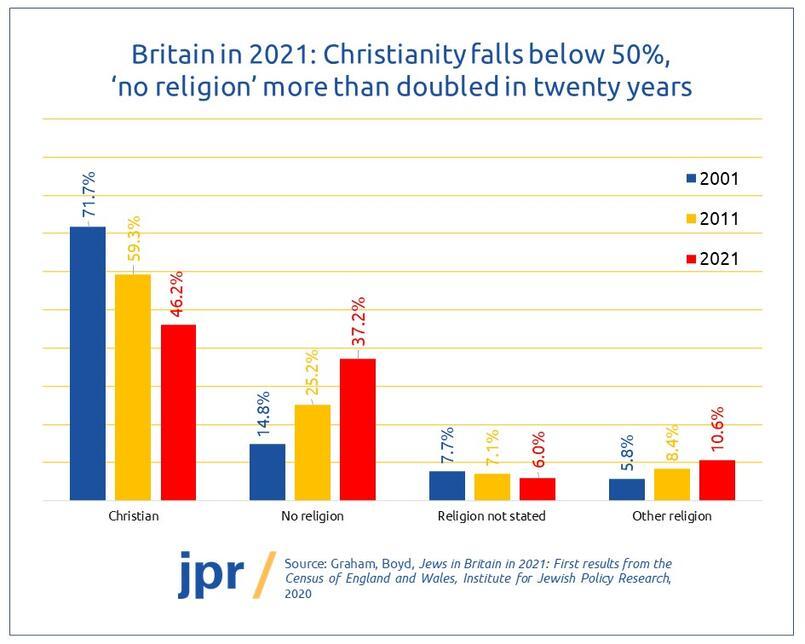

The big story from the newly-released religion data from the 2021 Census has nothing to do with Jews – at least, not at first sight. Twenty years ago, in 2001, self-identifying Christians made up 72% of the population of Britain; by 2021, that proportion had fallen to 46%. That happened for two main reasons – declining levels of engagement in Christianity, certainly, but mainly simple natural demographic change – the older Christian generation dying out, being replaced by a new, younger generation brought up without a religion at all.

But the reality now is clear: for the first time in over 1,000 years, Britain is no longer a Christian majority country – there are fewer Christians in Britain today than there are non-Christians. Symbolically, it’s a watershed moment that potentially has huge implications for our national traditions and institutions, many of which are steeped in Christian imagery and ideas. And that probably means increasingly vocal calls for change which, while welcome for some, will feel deeply unsettling to others. That feeling that people no longer recognise the country in which they live can create profound feelings of displacement leading to considerable social and political turmoil. How the country handles this new reality will be a true test of its values of tolerance and religious accommodation.

Alongside the decline of Christianity is the rise of those claiming ‘No Religion’ – from 15% in 2001 to 37% in 2021. Again, a key reason for this is natural change, but what it means is that fewer and fewer people are being brought up in any type of religious community, or with any substantive understanding of religious customs or ideas at all. And a good proportion of them are not terribly neutral about this; on the contrary, it seems to be ever more common to hear criticism of religion as an archaic, abusive and belligerent force based on no more than fairy tales. That reality potentially points to a more hostile environment for those who value their religious identities, the vast majority of whom do so because they find meaning, community and moral purpose in them. Again, the scope for feelings of displacement and alienation, and the accompanying tension that can cause, is clear.

Beyond both of these trends is a comparatively small, but nevertheless significant and growing population that associates with a religion other than Christianity. Together, they comprised 6% of the population of Britain in 2001; by 2021, that proportion had climbed to 11%. The growth can be seen in almost all of these groups: Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, as well as many other smaller and lesser-known religious communities. The one exception is Jews who, whilst exhibiting small signs of growth, are essentially stable. But together, these groups are combining to create an ever more multicultural society – increasing numbers and proportions of people living in Britain identifying with traditions and customs that are still rather new to the country as a whole. And this raises critical questions about religious accommodation – to what extent should Britain adapt to accommodate non-Christian, non-secular communities, and to what extent should minority religious communities conform to fit in with British norms? And further, if there is an expectation that religious minorities will conform to become more ‘British’, what exactly does ‘British’ mean, given the tremendous shift taking place from Christianity to atheism? Again, the scope for tension is obvious.

There is a specific Jewish angle on all of this. Jews can find themselves within all three of these trends. Like the Christian population, part of the Jewish population is declining through a combination of assimilation and natural change. Like the ‘No Religion’ population, part of the Jewish population is being brought up as completely secular, or is turning its back on Jewish religious customs and ideas, and choosing to live a largely secular life. And like the ‘Other religion’ group, part of the Jewish population – the most strictly Orthodox – is growing rapidly, driven largely by high fertility and normal mortality. Indeed, it is the combination of all of these factors that accounts for the current stability, or slight growth, of the Jewish population as a whole.

So the trends we see within the Jewish community are a kind of microcosm of the religious trends we see in Britain as a whole. All of the questions and challenges around religiosity in Britain can be applied directly to British Jews too. How we deal with them, both within the Jewish community and within Britain as a whole will have a major bearing on all of our futures.

Executive Director

Executive Director

Jonathan has been Executive Director of JPR since 2010, having previously held research and policy positions at the JDC International Centre for Community Development in...

Read more